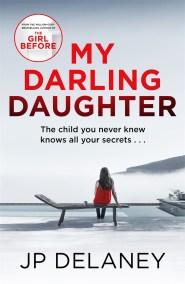

Read an extract of My Darling Daughter by JP Delaney

The much-anticipated new thriller from the bestselling author of The Girl Before, JP Delaney, publishes next week and in anticipation of the new book, My Darling Daughter, Crime Files is delighted to share this extract from the beginning of the book.

ONE

Gabe

It all starts with a message on social media.

In itself, that’s not unusual – Susie gets at least a dozen of those every day; more, if she has a gig coming up or the band have just streamed a new track. She usually lets a few accumulate, then sits down and answers them in one go. Hi – thanks for getting in touch!

We love hearing what people think about our music . . .

But this one’s different. This is like someone’s just ripped off her skin and exposed a fifteen-year-old wound.

Hello Susie. My name is Anna Mulcahy, although the name I was born with was Sky Jukes. I am 15 years old. If you had a baby girl in St George’s hospital on 6 March 2007 at about 5pm who was later adopted, could we perhaps meet? I believe you may be my birth mother.

Best wishes

Anna

Which in itself is devastating enough, but the kicker – the bit which causes her to run into my studio, ashen-faced and choked with tears, mutely holding out her iPad for me to see – is the final line:

ps: i am desperately unhappy

TWO

Gabe

She had Sky long before I met her, when she was twenty and just starting to get bookings as a backing singer. It was an unplanned pregnancy, the result of a casual relationship. In those days, most of the work for backing vocalists was on long tours, and a baby would have meant giving up the career she loved. That was before she knew she had fibroids, of course. Now, after five miscarriages and umpteen anxious waits between periods, she wishes she’d made a different choice.

Putting a baby up for adoption . . . People assume that, if you choose to do it, you can cope with the consequences. They don’t realise that you make the decision long before the baby’s born, when you’re still trying to be rational, to make plans, to get things right. When you tell yourself you could be making a childless couple’s life complete, as well as giving your child a better life. When things like careers – and, yes, the parties and fun any twenty-year-old enjoys – loom so much larger.

They don’t realise that, when you actually do it, it can be like a death. A death you feel responsible for, because you played the biggest part in it. A death you grieve a little more every year, because your imagination torments you with the knowledge that your child is out there somewhere – that you might glimpse her in the supermarket one day as you pick up a tub of ice cream, or see her swinging her legs at the back of a bus. In some ways, it can be even worse than a child dying for real.

I know, because that happened to me. I lost Leah to childhood leukaemia when she was almost three. It was unspeakable and devastating, and it crushed my first marriage as surely as if someone had smashed a rock on it. But it was also final – there was no going back, nothing to debate; only a slow, agonising coming to terms with it. It was different for Susie. Giving up her baby meant she always had that cruellest of emotions, hope, even if it was mixed with despair. A part of her has always wondered: What’s Sky doing today? Has she learnt her alphabet yet? Has she learnt to swim? Has she had her first kiss?

When people ask how we met, we sometimes joke that Susie was my groupie. At the time, I was . . . well, not exactly a household name, but the band I was in, Wandering Hand Trouble (I know – it was our label’s suggestion; you’d never dream of calling a group that now), had made the transition from boy band to mum rock without too much difficulty. We were on the verge of amicably going our separate ways, keen to enjoy the money we’d made while we still could. Going, Going, Gone was our farewell tour, Susie one of the backing vocalists.

What we don’t usually tell people was that one night I found her crying backstage and stopped to ask what was wrong. It turned out it was Sky’s sixth birthday. She told me a little of her story, I told her about Leah, and we bonded. Not exactly rock and roll. We do have some of the rock-and-roll trappings, though. Home is a beautiful farmhouse just outside London, with a couple of horses, half a dozen chickens and a rescue mutt called Sandy.

We’ve made the interior light and modern, the walls lined with canvases by young British artists. There are six bedrooms – when we looked round, the sellers were keen to let us know what a great family home it was, and how many children did we have? Neither of us ever knows quite how to respond to that question, so the answer sometimes comes out more tersely than we mean it to. When I said, ‘None,’ they muttered something about the space being great for parties, too.

Outside, there’s a small barn I’ve converted into a studio – for making demo tapes, not full-scale recordings; my day job now is writing songs for younger musicians. The chances are you’ve heard my work dozens of times without realising it wasn’t penned by the winsome singer-songwriter performing it. It’s a tragedy Susie and I don’t have kids of our own, of course – it’s particularly hard on her, since she’d make a brilliant mum and it’s the thing she longs for more than anything. But there’s still time, and, if there’s a silver lining, it’s that she’s finally fronting her own band, a folk-rock ensemble that’s just making the leap from pubs and clubs to being the support act at larger venues. There’s no money in it, of course – there’s no money in anything to do with music anymore – but she loves it, and I love that, when I go to watch, people hardly ever recognise me now; I’m just the supportive partner standing at the side of the stage. I wrote a ballad for them, ‘Lullaby for Leah’, that became a small hit on the streamers, and my heart is never so full of love as when I’m standing in the dark, watching her sing those words of mine, all the different sides of my life connecting in one ecstatic, emotion-laden instant.

So when she runs into the studio without even looking through the soundproof glass first to see if I’m in the middle of a take, I know instantly that something’s happened – something big. It’s with a feeling of dread that I start to scan the message. And although when I look up and meet her eyes I can see there’s actually a mixture of emotions there – fear, yes, as well as shock and concern, but also overwhelming elation that this moment has finally come – my own feeling of dread doesn’t lessen. Children or no children, we’ve achieved a fragile contentment, and I’m terrified it’s all about to come crashing down.

THREE

Susie

Gabe’s first question was, ‘Are you sure? It’s definitely her?’

I nodded – all I could manage.

‘But . . . how does she know? All these details.’ He read the message again. ‘Your surname. Even the time of birth.’

‘They have this . . . document.’ I took a breath. ‘It’s called a Later Life letter. The social worker writes everything down – about me, the birth, the adoption process – so the child knows where they came from. It’s given to them when they’re old enough to understand.’

‘But she isn’t meant to get in touch with you, is she?’

I shook my head. ‘The birth certificate’s sealed until she’s eighteen. But let’s face it, I’m not exactly hard to find. Particularly if the social worker mentioned that I’m a singer.’ Like any band, being active on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter is how we drum up publicity.

Gabe frowned. ‘So presumably we’re not meant to reply, either?’

‘Well, I’m not going to ignore it.’ I spoke more sharply than I’d meant to. But Gabe, big-hearted though he is, has surprisingly law-abiding instincts for a musician. ‘Apart from anything else, she needs my help.’

‘Well . . . she’s asked for your help. Which may not be quite the same thing.’ He caught my look. ‘She’s a teenager, Suze. Being melodramatic is what they do. I know I was, at that age.’

‘She’s contacted me. Like you say – she’s not meant to, so it must be something massive to have made her do that. Besides . . .’ I stopped, too overcome for a moment to go on, then said quietly, ‘I’ve waited fifteen years for this. There’s no way I’m letting her slip through my hands now.’

FOUR

Anna

Shit shit shit.

The moment I press Send, I look at the message and realise it’s terrible. That PS – I sound like a stereotypical whinging teenager, just another self-obsessed snowflake who’s upset because her parents won’t let her watch Love Island or something. I should have been less needy, trusted that she’ll want to meet me anyway. Or will she? Maybe she hasn’t given me a moment’s thought in fifteen years. Maybe she’s got her own happy family now, cute-looking kids half my age who she hasn’t put on Insta or Facebook for privacy reasons. Maybe her response is going to be some curt, chilly put-down. Thank you for your enquiry. Please do not contact me again.

I am sure it’s her, though. The stuff in the social worker’s letter made her easy to find. And when I saw her band’s feed, there was no doubt. Wow. She looks just like me. A much cooler version of me, if I’m honest – her strawberry-blond hair cut in a stylish short fringe, her teeth white and straight as she almost swallows the microphone reaching for a high note, her discreet diamond nose stud glinting in the stage lights. I look at the butterfly tattoo on her tanned, toned shoulder and think, My God, is that really my mum?

She couldn’t be more different from the woman I’ve been calling Mum if she tried. She’s about twenty years younger, for one thing. But it’s her smile that takes my breath away. In almost every picture, she’s beaming. Mum doesn’t have to do anything to make an expression of sour disapproval settle on her face – it’s there all the time, at least when I’m around.

Ever since I told her what’s really been going on with the man I’m forced to call Dad.

Susie Jukes. I roll the name silently around my mouth. She’s married now, but she hasn’t taken his name. He looks even cooler than her – Gabe Thompson, short for Gabriel. If you google him, you get page after page of hits, fans gushing over how good-looking he is. Mostly from about twenty years ago, but still.

Will they want to talk to me?

Will they believe me?

Might they even love me?

Try not to get ahead of yourself. The fact you’ve made contact is massive enough.

Plus, she’s really busy right now – they’ve got a big gig at the Roundhouse tomorrow. As support act, admittedly, but the last time they played in Camden it was at a pub called the Dublin Castle. I know all about her music. I’ve scrolled right back to the beginning of her feed, when Silverlink was formed, two years ago.

I’d love to show my support by clicking on the event – 371 people are interested – but if I do, the monster will see it. That’s right: he insists him and Mum are my friends on social media.

So we can keep you safe, Anna. So we can see when you start to indulge in risky behaviours.

Of course, that isn’t the real reason. He doesn’t want me posting about anything to do with home.

The way he handled the social worker’s letter was typical. On the very first page she put, The exact timing of when you’ll get this is up to your parents, but I’ve written it assuming you’re about twelve. Some parts you may find upsetting, so I recommend you show them once you’ve read it, so you can talk about it together . . .

About twelve? So apparently it never crossed her mind he might wait another three years, then just walk into my room – he does at least knock now, but he barely waits for an answer – and toss the papers on to the bed as I was doing my homework.

I looked at it. ‘What’s this?’

‘A letter. From the social worker you had at the time of your adoption.’

There was no envelope, just a thick sheaf of folded pages. ‘I see you’ve read it.’

‘I’ve checked it through, yes. To make sure there’s nothing that might cause you harm.’ His eyes were cold. ‘In any case, there wasn’t anything I didn’t already know.’

‘Why didn’t you give it to me before?’

‘It was never appropriate.’ Which was another way of saying, Because I wanted to exert maximum control.

‘Well?’ he asked impatiently, when I didn’t pick it up. ‘Aren’t you going to read it?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I am.’

I waited for him to leave. He waited for me to pick it up. Pointedly, I put my earbuds back in and picked up my homework.

He shrugged. ‘In your own time, then.’

It was a crap last line, but it clearly mattered to him that he’d been the one to deliver it. Out of the corner of my eye I watched him go, careful to keep my expression blank until the door was completely closed. But already a surge of excitement was coursing through me.

Maybe I can use this to find her. Maybe she can help.

‘Thrilling from beginning to end – I couldn’t turn the pages fast enough’ CLAIRE DOUGLAS

‘Absorbing and fast-paced’ KARIN SLAUGHTER

‘Excellent – domestic noir in all its darkest shades’ CARA HUNTER

The child you never knew

knows all your secrets . . .

Out of the blue, Susie Jukes is contacted on social media by Anna, the girl she gave up for adoption fifteen years ago.

But when they meet, Anna’s home life sounds distinctly strange to Susie and her husband Gabe. And when Anna’s adoptive parents seem to overreact to the fact she contacted them at all, Susie becomes convinced that Anna needs her help.

But is Anna’s own behaviour simply what you’d expect from someone recovering from a traumatic childhood? Or are there other secrets at play here – secrets Susie has also been hiding for the last fifteen years?

‘A twisty, electrifying read’ WOMAN’S OWN

See what everyone is saying about JP Delaney, the hottest name in psychological thrillers:

‘DAZZLING’ – Lee Child

‘ADDICTIVE’ – Daily Express

‘DEVASTATING’ – Daily Mail

‘INGENIOUS’ – New York Times

‘COMPULSIVE’ – Glamour Magazine

‘ELEGANT’ – Peter James

‘SEXY’ – Mail on Sunday

‘ENTHRALLING’ – Woman and Home

‘ORIGINAL’ – The Times

‘RIVETING’ – Lisa Gardner

‘CREEPY’ – Heat

‘SATISFYING’ – Reader’s Digest

‘SUPERIOR’ – The Bookseller

‘MORE THAN A MATCH FOR PAULA HAWKINS’ – Sunday Times