An extract from Erin Kinsley’s MISSING

Ash grey on white, a herring gull drifts against the clear June sky.

Alice lies back in her deckchair, letting the bird bring to mind music long not thought of, not heard for years: the dreamy, chilled melody of Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Albatross’. The guitar rings in her head, the background score to childhood memories of watching Top of the Pops in that cramped, unhappy house, her father oozing disapproval of long hair and loose morals from behind his evening paper, her mother darning his socks, bravely defiant and tapping her foot to the songs she liked.

The gull wheels away, out over the sea, which is, for once, the ultramarine blue of Enid Blyton story-book summers, a once-upon-a-time background for shrimping nets and sandcastles, for jam-sandwich picnics and Thermos flasks of lukewarm tea. A boy runs excitedly up the beach, a plastic bucket full of seawater slopping over his naked legs; a teenage girl throws a ball for an overexcited dog. As his grandkids bury his feet in a hole in the sand, an old man smilingly rolls his trousers up to his knees.

Alice’s own picnic is made up of foods she chose as her favourites, but the thought of the prawn sandwich makes her nauseous, and the pink-and-yellow Battenberg cake is claggy in her mouth. The first cocktail, though, is still well chilled in the cooler bag.

She drinks the whole can down.

When she was the same age as the running boy, she used to come here with her grandpa, holding his hand as he taught her how to read the sea, watching the wave patterns alter as the tide began to turn. Those changes are evident now. She glances at her watch: 3.15 p.m. Twenty minutes past high tide. God knows there’s no hurry. For a while longer she sits on, feeling the sun on her forearms, pulling up the hem of her sundress to expose her thighs to the heat. The days when she had legs men would drool over are long gone. Now she can’t even imagine how it would feel to be admired, pursued, desired. The water is retreating, leaving the glistening sand studded with pebbles and pearly shells. As the exposed beach grows wider, Alice watches pools emerge at the base of the groyne. In similar pools she used to paddle after scuttling crabs and – with Grandpa’s guidance – hunt for razor clams. She has a mark in mind. When the sea falls back level with the fourth seaweed-covered post, it will be time.

All that remains is the second cocktail. Pulling it from the cooler bag, she pops the cap and raises the can to the sky. A toast: to everything that’s been, good and bad; to whatever’s to come, to face it with courage; to her blessed, beautiful girls, lights of her life, may they forgive her. She drinks down the fizzy sweetness, then gets up from the deckchair to pack away her picnic. When the cooler bag is zipped, she removes the watch from her wrist. It was a wedding-day gift from Rob, always treasured and cared for, and she touches its face to her lips before placing it on the chair’s striped fabric. Pulling her black sundress over her head, she folds it and lays it over the watch.

Her new swimsuit is in bright shades of scarlet and fuchsia, an uplifting fabric that causes a pang of regret for her wardrobe full of dark, downbeat clothes. Other paths could have been taken. Different choices might have been made. But in the long run, different wouldn’t necessarily have turned out better.

Down the beach, the water has receded further. Soon it will reach a stretch of mudflats, which must be avoided. Removing her glasses, she folds them and lies them on top of her sundress. The gold ring on her left hand has grown too tight; before today, she can’t remember when she last wore it. The girls might like to have it, and yet she’s reluctant to leave it behind. She decides to take it with her, wherever she’s going.

Over and over, a voice in her head whispers, Why not go home? But home has become a nest of insoluble problems. Home is no haven, but a snare.

The alcohol is going to her head, but bringing melancholy rather than the care-less euphoria she intended. As she heads down to the sea, the loose sand is warm under her bare feet, though her legs feel heavy. Weaving between family groups surrounded by their paraphernalia, a lump rises in her throat. Frisbees, racquets and crabbing lines, damp towels, wet dogs and suncream: all were part of her life, once. She remembers Marietta, four years old and skinny, skipping prettily down to the sea, pursued by toddling Lily, plump and naked, always anxious not to be left behind.

Those were good times.

At the waterline, the sand is hard, and the cold water runs up over her feet, turning them blue-white, like Arctic ice. Alice turns her back on the sea, and sees through the flattering blur of her myopia the familiar view of the town: to the west and east the cliffs, the harbour with its boats between, and the gift shops, pubs and cafés along the quay. On the rising land behind is a spread of traditional Cornish cottages, white-walled and slate-roofed, matted together along the narrow lanes. And somewhere among them, close to where a church tower rises, is Alice’s house.

Think of the girls. Just go home.

She turns back to the sea and wades in, pushing through the breakers. A big wave – a seventh wave – rolls towards her, already curved and foaming as it prepares to break, just about where she is. A woman paddling with a small child is watching, and to her, Alice doesn’t seem afraid as she summons the guts to dive through the wave, reappearing moments later further out.

She’s out of her depth. Treading water, bobbing over rollers that break inshore from her, she runs her hands over her face to wipe the stinging salt water from her eyes. Then she faces another wave, which will certainly break before it reaches her. The woman watching is concerned now, but Alice takes the dousing and surfaces again, beginning to swim out away from the beach until she reaches the undulating swell beyond the breaking waves. She’s in a place where no casual swimmer should be, lonely territory haunted by precocious currents and riptides.

Still she keeps swimming out, making for the line where the sea meets the sky.

The woman watching takes out her phone.

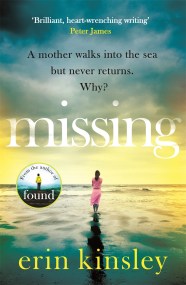

CAN TWO SISTERS SOLVE THEIR MOTHER'S DISAPPEARANCE?

'This may be the perfect staycation read' THE TIMES, Thriller of the Month

'Brilliant, compelling, heart-wrenching writing' PETER JAMES

One perfect summer day, mother of two Alice walks into the sea . . . and never returns.

Her daughters - loyal but fragile Lily, and headstrong, long-absent Marietta - are forcibly reunited by her disappearance.

Meanwhile, with retirement looming, DI Fox investigates cold cases long since forgotten. And there's one obsession he won't let go: a tragic death twenty years before.

Can Lily and Marietta uncover what happened to their mother? Will Fox solve a mystery that has haunted him for decades? As their stories unexpectedly collide, long-buried secrets will change their lives in unimaginable ways.

A gripping and emotional new thriller perfect for fans of Cara Hunter, Heidi Perks, Claire Douglas and Linda Green.

Praise for Erin Kinsley:

'Brilliant, compelling, heart-wrenching writing.' PETER JAMES

'An unputdownable thriller.' ELLY GRIFFITHS

'Sensitive and moving...but with a core of pure tension' SUNDAY TIMES

'Full of twists and turns to keep you guessing, this is a gripping and compelling read you won't want to put down' HEAT

'One of those rare finds - a page turner that is equally remarkable for the beauty of the writing. It will suck you in and take you on a journey' JO SPAIN

'Gripping...once started, impossible to put down!' MINETTE WALTERS