The importance of research for William Shaw’s The Trawlerman

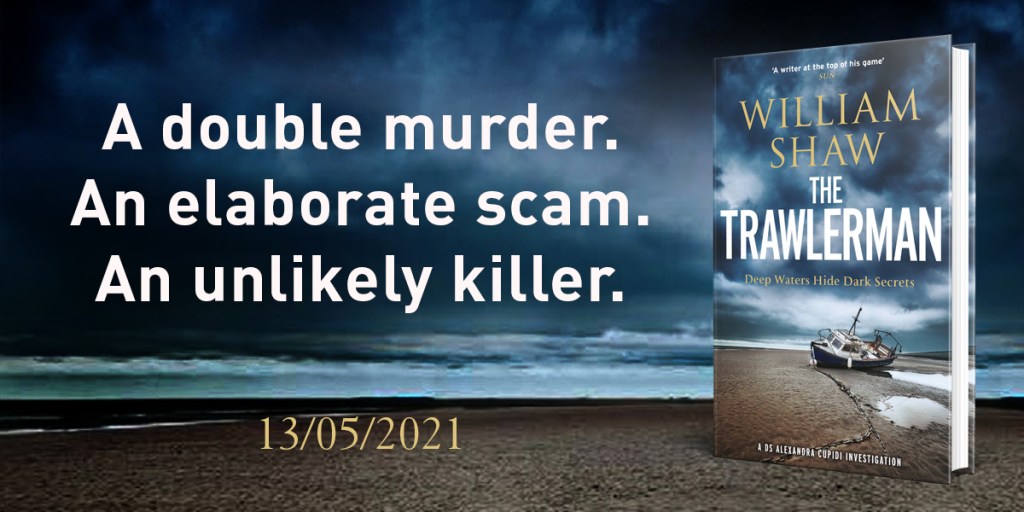

Ahead of the publication of his new novel, The Trawlerman, William Shaw reflects on the research he undertook for the book and why it is so important to his crime fiction.

Years ago, I was speaking to a woman who sold fish in one of the arches on the front at Brighton. She said she’d been a fishmonger most of her life. She’d been married to a trawlerman once, but he was lost at sea.

She was sitting on the stone bench outside her fish shop. I mumbled commiserations.

‘They never found his body,’ she told me.

It turned out that the woman had been in love with another man but though she was now alone, she couldn’t marry him because her husband was not officially dead – he was just missing. The law required her to wait for seven years before they could declare him dead and let her get on with her life.

Some stories just cling to you. It was many years later I was sitting in the garden of some friends of mine in Dungeness, when I started typing what turned out to be the first chapter of The Trawlerman. I looked up and saw a train arriving over the shingle at the tiny light railway station. For no particular reason, I pictured a wedding party arriving on the train and started writing that down. And then I remembered the woman from Brighton – and her seven-year-delayed nuptials – and over the next few hours, scribbling away, I realised I had the plot for a book, born of that one true story.

Trawling is an industry that has taken a lot of knocks, some maybe self-inflicted, but it’s still a big part of many of our coastal communities and if I wanted to write about it, I wanted to get the detail right.

Research is a big part of crime writing – for me and may other writers.

For me there are two reasons for that. The first is utterly selfish. I enjoy the excuse to learn new stuff and each book is an adventure that way – as I hope it is for the reader too. When it came to writing The Birdwatcher, I loved talking to birding experts about the realities of being a birdwatcher. They were generous with their time, making sure I was able to get the details right. When I started Salt Lane, set in Romney Marsh, one of the first places I visited was the prosaically named Romney Marsh Internal Aria Drainage Board – actually two men in an office outside Rye. They passed on a wealth of detail about both the modern practicalities of keeping the sea from overrunning that low flat land, but also the rich history of the marshes. When I wrote Grave’s End, I delved into the curious world of badgers – a species we live alongside but about which we know surprisingly little, and was delighted to find that one of the world’s leading experts in the species lived only a few miles away.

When I tempted this professor out for a meal to pick his brains, one of the first things he said to me was, ‘William. I hope you’re not going to attempt to write from the point of view of badger…’

Yes, well. I don’t listen to ALL the advice experts give me.

The second reason why research is so important to a crime writer is that we need to convince readers of the world we are building for them.

Whatever we read in the papers, we live in one of the safest periods of history there has ever been – if you’re white and educated at least. A crime writers’ job is to make readers believe that that isn’t always the case. We need to convince them that

skulduggery of all kinds can happen. That’s why so many crime writers meticulously research the facts their plots are based on. Because if you get a single detail wrong, their faith in your world will vanish.

Research builds trust.

I’m friends with the great writer CJ Sansom. I once witnessed him spent two weeks tracking down an academic who could tell him what Norfolk sheep looked like in Tudor England. When I finally read the resulting book there was only one brief mention of the appearance of the farm animals. A single sentence. But that wasn’t the point. That detail was one of the thousands of reasons why, as a reader, I trust every other sentence of the book.

So it was, last May, I found myself at sea on a trawler called The Valentine, skippered by a young man named Luke. We had set off from Folkestone earlier in the evening, heading south-west towards the fishing grounds off Dungeness.

This was night fishing; normally he would sail alone. It is not hard to see that this is dangerous work.

I stood, bracing myself against the roll of the boat with a notebook in one hand as he worked through the night, writing notes about the way he worked and looking at the fish as they were pulled, gasping from he sea.

The first thing I asked him directly was the hardest. ‘The thing is, I want to know how easy it would be to lose someone overboard. And for the body never to be found.’

Luke took a second before answering and I worried that I had already overstepped the mark. This is his livelihood, after all. Then he answered, ’Quite easy. That’s what happened to my grandfather.’

And he told me a story too, about how his own grandfather had fallen overboard – just like the husband of the Brighton fishmonger. His grandfather’s body was found weeks later in Belgium by pure luck; but it might have well have vanished forever.

It wasn’t until the sun was up that we turned and headed back to port. Our stories sit half way between fantasy and reality, relying on both. I think this is the great power that contemporary crime fiction has right now; it is not just fiction. It is more than that.