Dorothy L. Sayers – Better than Christie?

Writer, broadcaster and journalist Barry Forshaw asks who really was the best writer in the British genre’s Golden Age…

As many crime fiction aficionados attest, Dorothy L. Sayers was a far better writer than her contemporary Agatha Christie, and her academic background allowed her to freight in serious literary concerns along with the more populist concerns of the crime thriller. Her protagonist, Lord Peter Wimsey, with his aristocratic manners and mien, may seem precious in an era of alcoholic, working-class coppers, but he still repays close attention in the 21st century.

Crime fiction came of age in the years between the World Wars, and produced a host of writers who gained enormous popularity. The most celebrated writer of the period, which many regard as the ‘Golden Age’ of detective fiction, was Christie. But many other female writers entered the lists, notably Margery Allingham and the novelist many claim as the most accomplished and ambitious of the era, Dorothy L. Sayers. Part of the reason for the long-term success of Sayers and co. was a change in the publishing industry, particularly the advent of the paperback, and, even more significantly, the paperback ‘original’. For a small amount, a gripping piece of fiction was available in its entirety, for the first time, replacing the old magazine serialisation marketing methods that Poe, Collins and Doyle were obliged to deal with.

The Five Red Herrings (1931) is a favourite novel of many Sayers admirers, but is subtly different from the books that preceded it – and those that followed. Here, Sayers attempted to diffuse the literary characteristics that she had been building into the form with a more calculated use of the mechanics of the detective thriller, including sharply drawn characters, ironclad alibis and very specific references to time and place as they affect the plot (one element readers of the novel always remember is the importance of timetables).

In other ways, too, The Five Red Herrings might be said to be Sayers’ return to the classical plotting elements of the detective form – not to mention something of a move away from the psychological realism she had begun to introduce in such books as Strong Poison (1930), which had added levels of extra veracity to the thinly developed character of Wimsey. Sayers made it clear that The Five Red Herrings was designed as an exercise in testing the ingenuity of the reader, providing the straightforward pleasures of the puzzle story, so central to a great deal of Golden Age crime fiction.

The basic plot (and no spoilers will follow!) – has Lord Peter on vacation in the Scottish Highlands and encountering a group of painters, one of whom is discovered dead at the bottom of a cliff. The book points up for the reader exactly the question that Wimsey asks the police about the murder scene – the fact that ‘something is missing’ – what is it? And in a further acknowledgement of generic conventions of the time, the six surviving painters all have considerable reason to dislike the unpleasant murder victim, Campbell. As the title suggests, of the six, five are the eponymous red herrings, and a particular pleasure of the book is matching wits with Wimsey in figuring out who the murderer is, despite the fact that their alibis all appear to be waterproof.

By this stage in her writing career, Sayers was less interested in the eccentricities that she had granted her signature character and kept such things at bay, stressing the detective’s fierce intellect. In place of the sometimes tiresome earlier mannerisms, she gives Wimsey a particularly acidulous and sardonic tongue, another of the considerable pleasures of the book. Many Sayers admirers (including this writer) still regard the later Gaudy Night (1935) as her greatest achievement in the detective fiction genre, but The Five Red Herrings (with its significant detail of a stolen bicycle) will always hold a place of affection in the libraries of admirers of classic British crime fiction.

Sayers also showcases her other long-term character, Harriet Vane, in Gaudy Night, and her tantalising relationship with Wimsey approaches resolution here. Harriet returns to Oxford after a decade in which she has become a novelist, has lived with a man, and has got over being accused of his murder (in Strong Poison). She becomes involved in the case of a prankster, a seemingly unstable individual who is making life hell for an entire Oxford college. Inevitably, Lord Peter also gets involved and forms a powerful team with Harriet to crack the mystery. The setting of Shrewsbury College is as cannily conjured as anything in the campus novels of David Lodge and Malcolm Bradbury, and while the central mystery remains the focus, Sayers is able to address such issues as identity and the worth of people’s jobs (notably the idea of women’s professions in the 1930s). The relationship between Harriet and Lord Peter is handled with immense assurance, and it’s not hard to see why, for many, this remains the great Sayers novel.

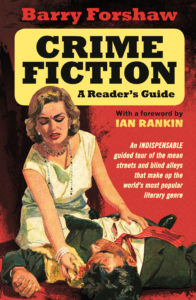

Barry Forshaw’s Crime Fiction: A Reader’s Guide is available to order now.