Out-Thinking Evil: On Creating Lincoln Rhyme by Jeffery Deaver

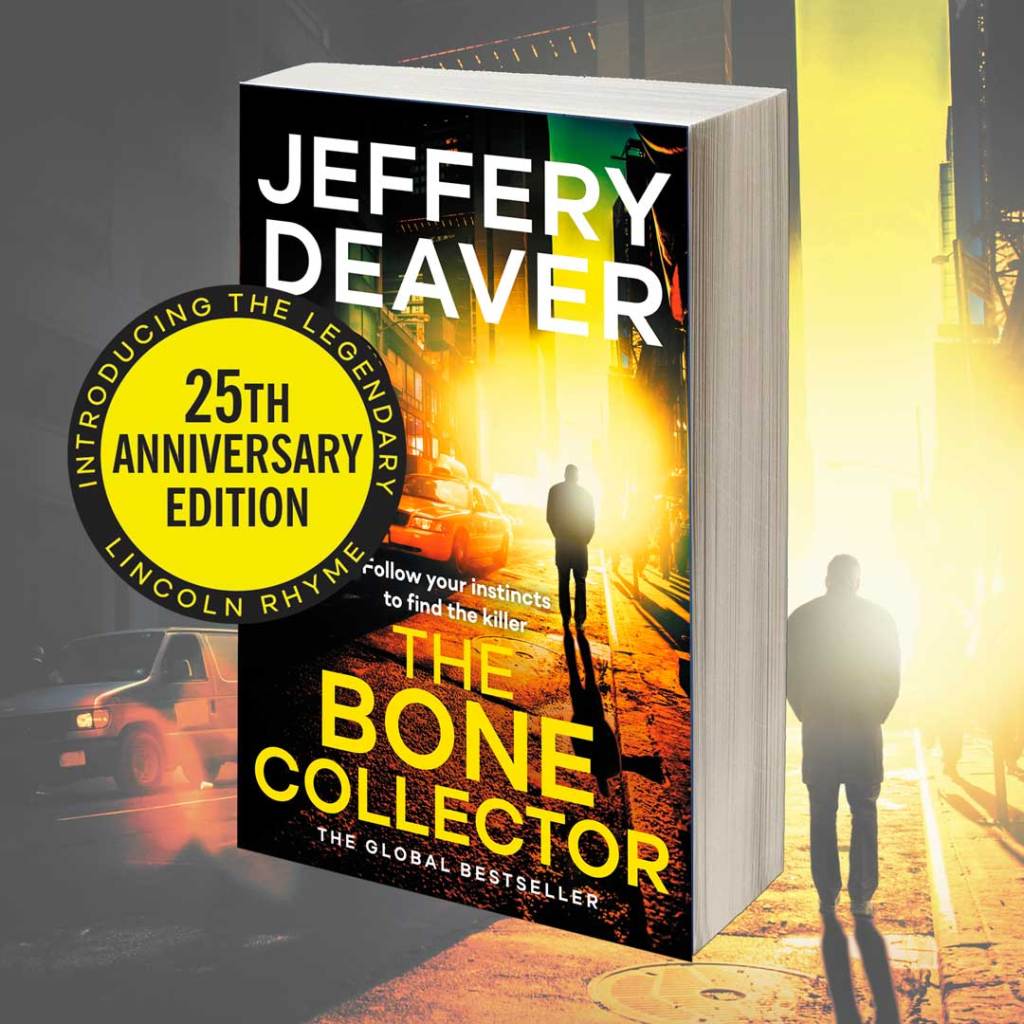

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of the publication of the global bestseller The Bone Collector, and to mark publication of our anniversary edition, Jeffery Deaver takes us back to the very beginning…

Out-Thinking Evil: On Creating Lincoln Rhyme

Jeffery Deaver

I have always preferred thoughtful crime solvers to those who save the day with guns and fists. I recall, years ago, watching some blockbuster thriller. At the climactic final scene the hero was being bested by the arch villain—kicked and slugged and tossed into the glass shelves of a laboratory (glass…always a lot of breakables in those scenes). Then guess what? He grabbed the pistol that he’d duct taped in some hidden spot earlier and blew the bad guy away. If the word had been in fashion then, my response would have been: “Meh.”

In contrast, take one of my icons of crime fiction, Sherlock Holmes. I found his out-thinking evil to be far more thrilling than a tale involving trial by muscle and firepower. Part of my interest, too, was that stories with heroes like Holmes, Poirot and Nero Wolfe required the author to craft clever plots that engaged readers’ minds, drawing them further into the story than if they’d just been witnesses to visceral thrills.

Some years ago I was casting about for a story idea and I found myself focusing on Holmes. I decided to use the character as a model for my next novel. I’ve always kept up on crime solving techniques and was aware of important new developments in forensics (I’m talking pre-CSI and its offspring), which was Holmes’s specialty. This would be an element. And so would his primary weapon: his mind.

So I immodestly set out to create a modern-day character who out-Holmesed Holmes. Doyle’s character, of course, got into the field with some frequency. He was a master of disguise and often carried a trusty Webley revolver. My character, on the other hand, would rely exclusively on his skills at forensics and powers of deduction to discover the antagonist’s identity and craft traps to snare them. As someone who has experience with nerve damage, I first thought of creating someone who was a paraplegic—whose body functioned above the waist. But I decided to go all the way and make him a quadriplegic, almost entirely paralyzed.

I believe our goal as authors, at least in the genre of entertaining fiction, is to craft stories in which realistic characters confront increasing levels of challenges, which are ultimately resolved to the readers’ satisfaction. Creating Lincoln Rhyme allowed me to tell stories in which my character constantly confronted and, as we’ve seen, overcame any number of challenges. The concept also challenged me as a storyteller to write credible and compelling tales featuring a protagonist somewhat different from those in traditional thriller fiction. And as someone who, like Lincoln Rhyme, abhors boredom, I have been delighted that this is the case.

The question often arises about the popularity of this singular character. Rhyme is the subject of 15 novels, a dozen short stories, a feature film and a TV series. And readers continue to want more. Why? I think the answer is that he’s an Everyman. Largely separate from his physical presence, Rhyme is his heart and soul and mind before anything else.

And can’t that be said of us all?

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of The Goodbye Man, discover Jeffery Deaver's chilling thriller that inspired the film starring Angelina Jolie and Denzel Washington and is now a major NBC TV series.

Their first case, their worst killer . . .

New York City has been thrown into chaos by the assaults of the Bone Collector, a serial kidnapper and killer who gives the police a chance to save his victims from death by leaving obscure clues. Baffled, the cops turn to the one man with a chance of solving them - Lincoln Rhyme.

Left paralysed by a debilitating accident, ex NYPD cop Rhyme has to dig deep into the only world he has left - his astonishing mind - to have any hope of solving the case. With the help of a young police officer, Amelia Sachs, he starts to close in on the killer. But as he edges closer to the truth, the Bone Collector is closing in on Lincoln Rhyme himself.

'This is a novel that will chill your blood on the warmest day of any summer holiday. Keep looking over your shoulder . . .' Independent on Sunday