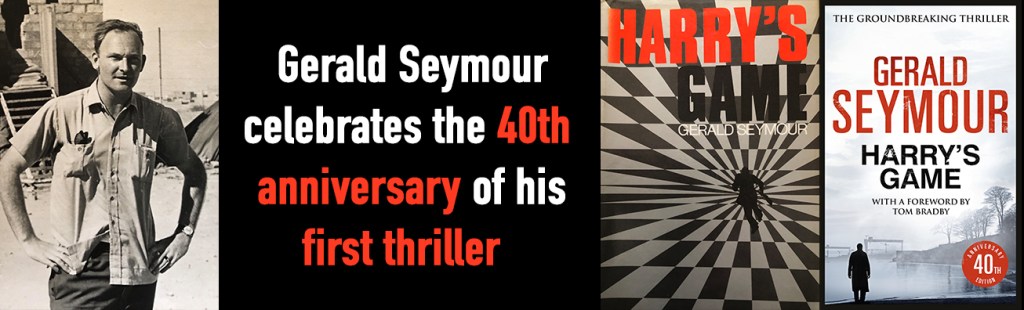

Gerald Seymour celebrates the 40th anniversary of his first thriller, Harry’s Game

‘See him, sir, that one – down there … ’ and a rueful grin played on the face of a young marine as he pointed down a slope and towards the shanty town on the edge of Tawahi district. A swarthy man wearing a filthy vest and a futah skirt covering his stomach and legs, was hammering nails into a wooden frame that supported a single sheet of corrugated iron, making a shelter. The marine’s voice dropped, ‘He’s one of ours, Special Forces.’

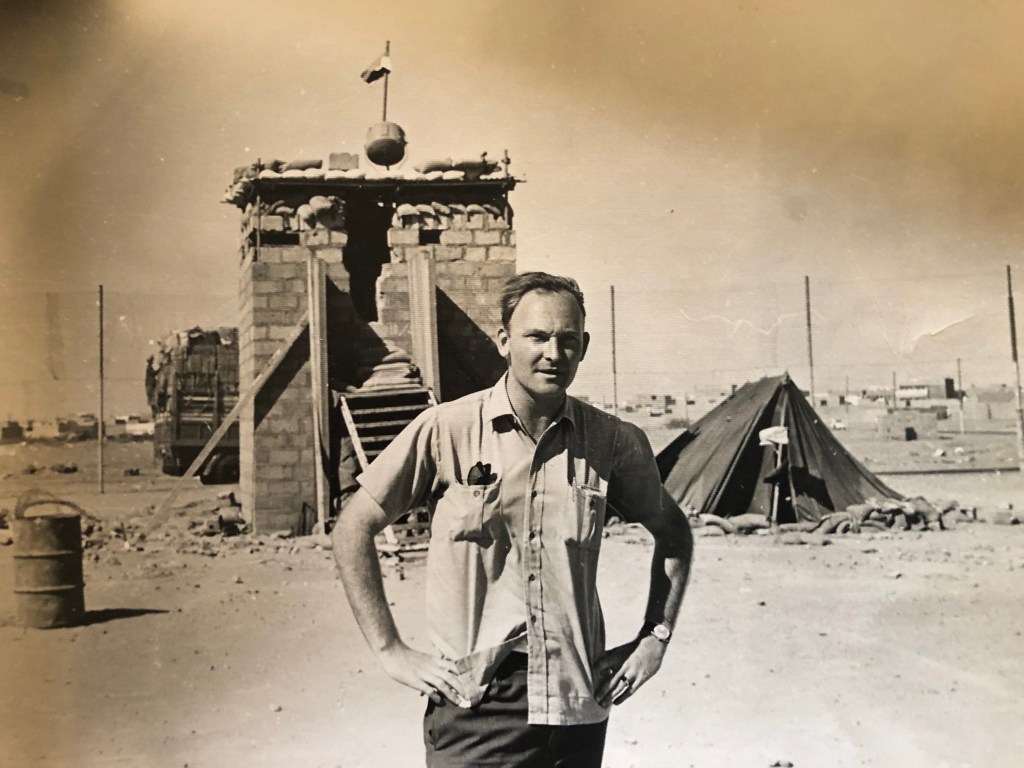

This was Aden where a vicious little war was being fought out between the local National Liberation Front, and the British military. How nasty, how dangerous? Four friends and colleagues had been shot down inside or on the front steps of my hotel that month. It was 1967 and I can still picture that man, who would have put his life on the line, working on his accommodation, from which he’d do front line surveillance. I’d already named him in my mind, he was Harry, and I feared for him. He’d have had back-up of a sort but its chance of successful intervention if the bad guys had come calling would have been remote.

Inevitable that when I started out on my first thriller it would be about Harry, my Aden man.

Gerald Seymour in Aden in 1967

I’d been brought up in a household dominated by books. My father, once a bank manager, had been Chairman of the Poetry Society and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and my mother had written more than 40 novels, the first published when she was 23. I was a News At Ten reporter and six years after Aden had that extraordinary life style of jumping on aircraft and going off to other peoples’ wars, a TV journalist’s dream career. I’d just returned from the Yom Kippur conflict, reporting from the Israeli side, and ITN said I was to take a month off before coming back into the office for another assignment. How to fill the time … I told my wife, Gill, ‘I’m going to write a novel’.

At that time, 1973, half the scribblers in London were trying to emulate Freddie Forsyth (ex BBC) and his phenomenally successful Day of the Jackal. I joined the queue. Gill went into Teddington and bought a small pine table, a £5 investment, and put it in our bedroom and I was forbidden under pain of death, or worse, to smoke while I was typing. The place I knew best in the world, my most frequent destination, was Belfast. . . so that was where my man, Harry Brown, would be flying into. The city, at that stage of the Troubles was a brutal place where mercy and charity were in short supply

I didn’t have an outline of the plot. I had no notes to work from. Just sat down and started hitting the keys, and was rustling up anecdotes and experiences from my trips to the Province, including my coverage of Bloody Sunday. I set out to write about the ‘ordinary’ people on both sides, and not to trumpet in any way the propaganda of army staff officers and Provo apologists. I hoped to tell a worthwhile story, but to inform and take an audience beyond newspaper reports and the snippets on the nightly news bulletins. . . and hoped it might one day be published.

I was about a quarter of the way into the story when I was packed off to Beirut to interview Yassir Arafat, the Palestinian guerrilla leader. First had to locate him. He did me a wonderful favour. I was staying at the multi-star Phoenicia Hotel on the sea front, and would go to the Arafat office every morning and every evening, and be told that he was in Damascus or Cairo or Baghdad or. . . but the next day might return to Beirut. He never did. The Foreign Desk in London indulged me for almost two weeks before pulling the plug. I had room service to keep me going and managed four coherent chapters – and had Harry well bedded down in savage Belfast.

In those times, the early Seventies, the military’s intelligence gathering was chaotic. Men trying to go undercover in the city were found and killed. I wanted to get under the skins of those people and the desperate risks they ran and the pressures they were under. Not only Harry but the assassin he was sent to locate.

I finished the story, typed The End and had a bad dose of cold feet. The pages went into a shoe box and stayed there for a few months before I sidled up to that much loved newscaster, Gordon Honeycombe, and asking his advice: what to do with it. He sent me to his agent, the top man in London, Michael Sissons. . . another thriller by another reporter, he had that look on his face when I placed it on his desk.

The first sign that something extraordinary was going to happen in my life was Gordon telling me that half a dozen bottles of champagne had been left on his doorstep and ‘Many thanks’ for the introduction.

The next tick in the box was a prominent US publisher reading the typescript on a flight back to New York and ringing from the airport to buy it, and he came up with the title, Harry’s Game. And another tick, in the States it was the Book of the Month Club main Selection for the Autumn. Heady stuff for a young reporter, and I was then 33 years old, and a debut author.

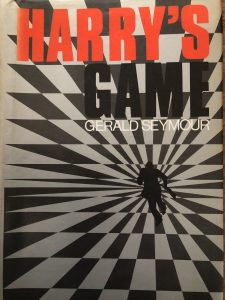

The original cover of Harry’s Game

The big accolade came from Freddie Forsyth who wrote, A thriller about the IRA which invokes the atmosphere and smell of the back streets of Belfast as nothing else has done that I have read. I was grateful for that and for the kind words of a suspense legend, Eric Ambler: One of those rare pleasures, a considerable novel that is also a superb thriller.

Some doubted that readers would want a Belfast story in those desperate days. This was highlighted by the experience of a New York film producer who bought the rights and flew to London. After checking into the Grosvenor Hotel he put on his TV: I led that night’s bulletin from the scene of the IRA’s assassination of Ross McWhirter. The next day the producer rang Nat Cohen, the vastly influential head of EMI movies, and told him, ‘I’ve bought this wonderful story of the war in Ireland – who should I go and see first?’ Cohen told him, ‘My advice, go see a psychiatrist.’

It was published on 3rd November, 1975, a pretty important date to me because it changed my life. I can’t say it flew off the shelves but it moved at a pretty useful pace … and the Metropolitan Police’s then Commissioner cleared out the stock in Hatchards, Piccadilly, and gave a raft of his officers the book for Christmas, and the Defence Secretary used it for his PPS’s present, and infantry units about to be deployed to Northern Ireland made it required reading for officers and NCOs.

Was it a ‘one-off’? That made me nervous, so I started within a few weeks on a second story which became The Glory Boys, and had no mention of Harry and his mission to Belfast. That became a TV mini-series with Rod Steiger and Anthony Perkins.

But before that Harry, played by Ray Lonnen, was made for ITV and became a platform for some young actors getting a foot on the ladder. Derek Thompson, later of Casualty, was Harry’s target, and Linda Robson (Birds of a Feather) was the tragic girl who couldn’t keep her mouth shut, and Charles Lawson (a star of Coronation Street) spotted the flaw in Harry’s accent. All had their big break, like me, from the story … and there was a quite mesmerising anthem from Clannad, the hugely talented Donegal group. The series reached the Emmy short list in New York but we were beaten by Olivier and Shakespeare – can’t complain – Lord Olivier was Lear!

I attempted to marry two lives, reporting and writing, managed it for a couple of years then took the big gulp and wrote my resignation letter. I hugely appreciated my time as a newsman at ITN which taught me how to get into dark corners, and survive, and how to open doors that should have stayed locked, but I believed I had gained a freedom to write and picture the world, warts and all, around me … and tell some truths that newspapers and TV and radio may not have space for.

What made Harry special is a question I cannot answer. I have no formula. Not then, not now. I’ve never believed in anything other than following instincts of how a story might work, flying on the seat of my pants – telling it as best as I am able. I hope I have more stories to write and consider myself lucky to have a publisher and readers – and my most sincere thanks go to that young marine of 42 Commando who showed me Harry under a baking Aden sun and in a place of high danger.

The special 40th anniversary edition of Gerald Seymour’s Harry’s Game is available to order now.